Unit History of

213 Assault Support

Helicopter Company

The Black Cats of Phu-Loi

CHAPTER TWO

PHU - LOI HISTORY AND EVENTS

Phu Loi Army Airfield, Vietnam

Latitude: 10° 59' 36.600N Longitude: 106° 42' 4.680E

Runway Length: 2900 feet PSP

Home to several units, Phu Loi Army Airfield, was located west of Ben Hoa.near the small native village about 25 miles northeast of Saigon.

Phu Loi airfield was a Japanese air base during WW2. Phu Loi Air Field was actually built using POW labor, during WWII. The Japanese had American POWS cut out the jungle and level that area, for their fighter planes to use.

PHU LOI Political Prisoner Camp, under President NGO DINH DIEM

In 1945 there was a prison at Phu Loi, housing political prisoners who supported Ho Chi Minh. In 1958 Phu Loi was a concentration camp under Diem. Prisoners were massacred here.

Phu Loi had a 1 mile defensive perimeter. Was triangular shaped with an artillery unit in each corner. Located approximately 30 kilometers northeast of Saigon, along National Route 13, Phu Loi was headquarters for the Big Red One’s Division Artillery, its armored cavalry unit (1st Sq./4th Cavalry), and other key division units.

Phu Loi had been the scene of fierce fighting during the 1968 Tet offensive. Major units of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) troops had used the area around Phu Loi for pre-Tet staging and as a jumping-off point for their attacks on Saigon and surrounding U.S. and South Vietnamese installations

When the fall of Saigon was planned, one of the northern thrusts was begun through Phu Loi.

March 9, 1968

The following is an edited version of an article titled "Gunships Kill Over 200 VC" dated 9 Mar 1968. Troop-carrying Slicks and gunships of the 173rd AHC and troops of the 1st Inf Div killed over 200 VC in seven hours of fighting during recent VC attacks near Phu Loi. Called upon to bring reinforcements to a unit engaged in heavy contact, the Robin Hoods, troop-carrying helicopters, picked up members of the 1st Div. and commenced what was to be a very short combat assault. The LZ, under intense rocket, machine gun and small arms fire, was only 1,100 yards from the end of Phu Loi's runway. The VC were dug in for a long siege of fighting. The Robin Hoods, rapidly picked their way through the hail of fire and dropped load after load of infantrymen into the battle zone. The foot soldiers and their supporting tanks fought their way across the large field in the VC replacements. After seven hours, more than 200 enemy bodies were counted.

The source for this information was 6803AR.AVN supplied by Les Hines

May 5-6, 1968

The II Field Force Vietnam quarterly ORLL reported that B/1/4 Cav of the 3d Bde, 1st Inf Div while conducting reconnaissance in force operations six kms SW of Phu Loi, contacted an unknown size enemy force. A/1/4th Cav reinforced and light fire teams of A/7/1st Air Cav supported. Enemy losses were 137 killed (66 credited to A/7/1st Air Cav). Friendly losses were 19 wounded. The following day, elements of the 1/4th Cav supported by artillery, airstrikes, light fire teams and AC47 (Spooky) continued to attack the enemy SW of Phu Loi, killing 303 while suffering four US killed . The source for this information was II Field Force Vietnam quarterly ORLL period ending 31 July 1968 from Walker Jones P:25

The airfield and compound were turned over the the ARVN's. Sometime in 1975 the area was stripped of the usefully building materials, basically wiped out. The latest information I have received the compound is still used for aviation as it is a communist helicopter facility and is closed to the public. I had information that a returning Vet tried to gain access to the air field and was denied. UPDATE: Primo Funari left this statement on the 1st Avn Bn RVN Guestbook, 09/17/2003 "I returned to Phu Loi twice doing the last 4 years. The base is now a prison and you are unable to get to the runway." Primo was an observer on OV-1's, 04/67-10/68.

(Not sure if this is true or not. I heard it was open to the public and is a training facility)

All Military Units Assigned to Phu Loi - 1965 - 1972

116th Aviation Company, 11th Aviation Battalion

128th Assault Helicopter Company

145th Aviation Battalion, Combat

165th Transportation Company

168th Combat Engineer Battalion

184th Aviation Company

1st Aviation Battalion, 1st Infantry Division

1st Aviation Brigade

1st Logistics Command

1st Squadron, 11th Armor Cavalry Regiment

1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry

205th Assault Support Helicopter Company

213th Assault Support Helicopter Company

242nd Assault Support Helicopter Company

2nd Battalion, 12th Artillery Group

2nd Battalion, 13th Artillery Regiment

334th Assault Support Helicopter Company

34th Battalion, 20th Engineer Brigade

362nd Aviation Company

520th Transportation Battalion

539th Transportation Company

Hat Pins are available at: http://w3.trib.com/~wrp/gicat11.htm#

Establishing Phu Loi

From October 21st to the 27th, the 2/503rd and B/3/319th cleared the area in preparation for the establishment of the 1st Infantry Division in that area and the establishment of Phu Loi base camp. (This info is a little sketchy)

In Search Of

SFC, E-7-HOANG VAN NGUYEN, service number 64A140731 ARVN army interpreter assigned to Troop D (AIR) First Squadron, Fourth Cavalry, First Infantry. Division based in Phu Loi, South Vietnam in 1969.

SFC Nguyen was born in North Vietnam and taught English in South Vietnam before the war.

Communists’ Statement

As early as the end of 1954, Ngo Dinh Diem committed heinous murders at Ngan Son, Chi Thanh, Cho Duoc, Mo Cay, Binh Thanh, etc. He launched many “denounce communist” drives, cracked down on the struggle of our compatriots in the South in a most maniacal and class revengeful manner. On 1 December 1958 he poisoned to death. thousands of our revolutionary fighters and compatriots detained at Phu Loi camp. In May 1959, he issued Law 10/59 to kill the patriots. From 1954 to 1959 there were 460,000 communists and patriots arrested, 400,000 jailed and 68,000 killed.

TET Tidbit

Just north of the city, the US. 1st Infantry Division turned the tables on the force that was supposed to block the Big Red One from reinforcing Saigon. Moving southeast along Highway 13, the Americans ran into the 273rd VC Regiment, the same unit that had hit the district capital of Loc Ninh the previous October. The VC took up defensive positions near Phu Loi but were caught there by the division’s artillery and sealed in the box by the infantry. Two days and 3,493 artillery rounds later, the 273rd had, been virtually destroyed as an effective fighting unit.

Visit Vietnam

Tours are available to Vietnam, even to Phu Loi base camp, which is now a training facility for the Red Army. Here are 2 sites sponsoring trips.

http://vietnamtourism.hypermart.net/vet.htm

http://www.discoveryvn.com/inbound2.htm

Action Around Phu Loi

The following is a account of the action around the Phu Loi base camp

during 1968. This account has been provided by David Hill, a member of the LRRP team that fought in this area.

Incident: LRRPs Hit NVA Battalion Near Phu Loi

Dates: 10-12 May 1968

Unit Involved: Co. F/52nd Inf. (LRP), 1st Infantry Division

While delegates began peace negotiations in Paris, the war in Vietnam once again flared up to new levels of combat. On May 5, 1968 communist forces attacked Saigon and 118 other South Vietnamese district and provincial capitals, major cities and allied military installations. The so-called “Tet II” or “Mini-Tet Offensive” attacks marked a sharp resurgence in communist efforts to carry the war from the border frontiers into the population centers of the South. At least eight NVA regiments and as many NVA “Infiltration Groups” (each a battalion-plus size unit) were now known to be operating within or moving into the area west, north and northeast of Saigon. With major enemy troop movements through War Zones C and D toward Saigon and its environs, the Long Range Patrol teams of Co. F/52nd Inf. (LRP) were now tasked to screen major bases in the Big Red One’s Tactical Area of Operations. On May 7, 1968, two Co. F teams, Wildcat 1 and Wildcat 2, were assigned the mission to aggressively conduct reconnaissance and ambush patrols outside of the major 1st Division installation of Phu Loi.

Phu Loi was headquarters for the Big Red One’s Division Artillery, its armored cavalry unit (1st Sq./4th Cavalry), and other key division units. Team Wildcat 1 was led by SSgt Jack Leisure and comprised of Assistant Team Leader Roger Anderson, Charley Hartsoe and Chris Ferris. Team Wildcat 2 was led by Sgt. Ronnie Luse and comprised of Assistant Team Leader Robert Elsner, Bill Cohn, Al Coleman, Dave Hill, and John Mills. The LRRP teams would be operating under the command and control of Division Artillery HQ. Surrounded by vast rice paddies (dry at this time of the year), rubber trees and the villages that supported those agricultural activities, Phu Loi had been the scene of fierce fighting during the 1968 Tet offensive. Major units of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) troops had used the area around Phu Loi for pre-Tet staging and as a jumping-off point for their attacks on Saigon and surrounding U.S. and South Vietnamese installations. Co. F (LRP) Team Wildcat 2, led by Sgt. Luse, had on January 31, 1968, spotted an estimated VC/NVA regiment attempting a night crossing north of Phu Loi from Dog Leg Village (named “Dog Leg” by the Americans, due to its “L” shaped appearance from the air) to An My, and conducted an artillery ambush against them, prematurely triggering the first Tet attacks against Phu Loi. After being nearly decimated by the artillery and air support called in by the LRRPs, the surviving enemy troops had escaped into the nearby village of An My, which itself became the scene of a vicious battle, as elements of the Division’s 1st Bn/28th Inf. and 1st Sq./4th Cavalry fought for the next few days to roust the communist force from the village. Ironically, Team 2 received credit only for spotting the enemy troops, the official “After Action Report” failing to mention that the LRRPs had actually remained in their ambush position and adjusted artillery and aerial fire on the NVA/VC force throughout the night of 31 January. The LRRPs withdrew to Phu Loi base camp only after the enemy had moved into An My.

1st Division G-2 (Intelligence) believed that, with the renewed attacks and continued sharp fighting in Saigon, the area around Phu Loi would again be a major transit route for the communist forces. With the VC Main Force units nearly eliminated during Tet, the communist forces were known to now be predominantly NVA, with VC Local Force soldiers acting as guides to move them through villages and way-stations to Saigon. G-2 and the LRRPs felt that they might again be able to spot major crossings of enemy troops near Phu Loi and hit them before they could get to their objectives either of Phu Loi itself or Saigon and major allied installations surrounding it. Increasingly, Co. F missions were being designed as long-range “ambush” patrols. Over the course of the previous year, the Co.F LRRPs, had transitioned from “sneak-and-peak” tactics to a policy of “hit ‘em hard every chance you get, with everything that could be brought to bear”. They were not to take suicidal risks, but opportunities to hit the enemy now superceded purely reconnaissance-type missions. The teams would have first call on available artillery and air support, and were not reluctant to use it. Many missions, like those the LRRPs were to conduct around Phu Loi, were relatively short-range; but with the numerous enemy movements near major allied bases, long-range, heli-borne missions were being used less frequently—and the enemy was no longer either elusive or only out in the hinterlands. While this strategy resulted in numerous and frequent clashes, with resultant large enemy casualties, it was eventually to result in increased LRRP/Ranger casualties as well.

Teams 1 and 2 began their short-range night ambush patrols from Phu Loi, walking out to positions ranging from two to five kilometers beyond Phu Loi’s bunker line, and using alternating exit points and patrol directions. One patrol started with a daylight truck ride to an Army Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) base camp about five kilometers from Phu Loi, followed by a night patrol and ambush back toward Phu Loi, the LRRPs arriving back inside Phu Loi the following evening. But initially, neither team was spotting enemy troops nor any signs indicating heavy NVA movement through the area. Out of sheer frustration, Team 1 had even sneaked in close to Dog Leg Village, placed a transistor radio loudly playing Vietnamese music on an adjacent paddy berm, and backed away to observe the sight through their starlight night vision scope—hoping to at least attract one or more curious enemy soldiers into range of their ambush. Nothing happened. However, G-2 and the two team leaders were still convinced that enemy troops were crossing the rice paddies at some point near Phu Loi, and decided that one team would go deep into the open rice paddy area between Dog Leg Village and An My Village, seeing if “lightning would strike twice” at the same crossing location Luse’s Team 2 had so successfully exploited on 31 January. Since it had been “Luse’s spot” in January, it was decided that Team 2 would take the first patrol to that area on the night of 10 May, with Liesure’s team standing-down that night, but available as a reaction force from Phu Loi.

Team 2 moved out of Phu Loi just after dark on 10 May, moving cautiously out to the same Chinese graveyard Luse’s team had occupied on 31 January, located approximately three “clicks” (kilometers) from the Phu Loi perimeter. The team carefully scoped the graveyard and then moved to the same stone grave monument structure (somewhat like a miniature pagoda) Luse had used on that first night of the Tet Offensive, and set up security around its base. Half of the team climbed up into the structure, which being about five feet off of the paddy, afforded them an excellent field of vision to the paddies all round their position. The starlight scope gave them unrestricted visibility for several hundred yards in all directions, and they began observation shifts. The focus was primarily to the north of their position, toward the Tet crossing site previously discovered by Luse’s team, which was the shortest open route between Dog Leg and An My. They settled in for the night to see what might develop.

At approximately 0100 hours, a squad-size unit of enemy was observed moving into the rice paddies north of the team’s position, having emerged from the wood line east of the team, which housed a part of Dog Leg Village, understandably expecting to move undetected across the rice paddies. Luse called in artillery, but no hits were made on the enemy, who quickly broke southeast back toward the hidden LRRP’s position, paralleling the tree line but still in the open rice paddy (perhaps thinking that the initial artillery rounds had only been unadjusted “harassment and intervention” [H & I] rounds). When the NVA/VC came within range of the team’s weapons, Luse ordered his team to open up on them with small arms fire. The enemy returned fire, but after several more exchanges, was able to break contact, finally disappearing back into the wood line and Dog Leg. The team had no casualties and they were not able to ascertain enemy losses, if any.

With an apparent night crossing area confirmed and their own position now compromised, Luse directed Team 2 to quickly move back to Phu Loi--it was time to “get out of Dodge”. Two-man “hasty ambushes” were dropped off periodically to surprise any pursuing enemy, the rest of the team stopping periodically to observe the paddies around them and let the stay-behind ambushers rejoin them. Luse radioed Liesure’s team, who had been in Phu Loi monitoring Team 2’s progress, and told them to “saddle up”, bring an ammunition resupply, and meet Team 2 at the Phu Loi perimeter to decide their next course of action. By the time the teams met just inside the perimeter bunker line, Luse was practically “doing a jig”, excitedly telling Liesure and his team that “we found the crossover point; same place as in January”. Luse and Liesure quickly conferred, decided to call it a night, and determined to get some sleep then meet later in the morning to plan the next patrol.

On the morning of 11 May, the teams conferred further, decided that the NVA were basically stuck in their same infiltration patterns past Phu Loi heading toward Saigon, and that the crossing point over the rice paddies

between Dog Leg and An My still offered their (NVA) units the quickest passage southward. Liesure and Luse decided that on the night of 11 May they would take their combined “heavy” team (ten LRRPs) back to the

Chinese graveyard one more time because: 1) they suspected that the crossing point was in continuous use by the NVA/VC units moving past Phu Loi; 2) the grave monument itself, with its height above the rice paddies

and stone structure, provided an excellent view of the entire rice paddy expanse and some protection from direct fire; and, 3) the NVA and the local VC would not expect any Americans to be crazy enough to utilize precisely the same ambush site (from which firing had been initiated by the LRRPs) two nights in a row. (CUT)

Events on the night of 11 May were soon to validate the LRRPs assumptions and strategy.

The combined teams included an M-60 machine gun carried by Elsner. Anderson, who carried the LRRPs only M-14E2 (full-auto M-14 rifle), which used compatible ammunition, acted as Elsner’s assistant gunner and carried additional belts of machine gun rounds. With the rest of the team members carrying extra grenades, claymore mines and magazines and rounds for their M-16s and M-79 grenade-launchers, the combined teams packed considerable offensive power—and they were looking forward to utilizing it if the situation allowed. Artillery and air support would provide the main punch, but the LRRPs could give a good accounting of themselves in a direct firefight as well.

That night they departed the Phu Loi perimeter, taking a different route out to the graveyard than they had the previous night. When approximately 300 meters from the graveyard, the teams halted while Luse and Liesure scanned the grave monument which would again be their observation post (OP) for the night. After scoping it and the surrounding area for ten minutes, seeing no movement or suspicious shapes, they starting the point man moving cautiously toward their objective. Reaching the monument at approximately 2300 hours, the teams quickly formed a small circular perimeter around the grave monument, intending to put claymore mines around their position. Each team member was assigned a portion of the perimeter as his primary security zone, and a rotating watch shift was set up among them for manning the starlight scopes up in the grave monument. Even with just the ambient light, the scopes afforded them remarkably clear vision out to several hundred yards, albeit in the ghostly green light inherent with the starlight scope.

The teams had not yet even gotten their claymores out, when Luse, up on the wall of the grave monument looking through his scope, whispered to Liesure that he saw a column of troops and a truck moving slowly from south to north, just inside the tree line adjacent to Dogleg village. Liesure quickly passed this information on to the other team members and climbed up next to Luse with his own scope, pointing it in the same direction as Luse’s. He confirmed that he also now could see “beoucoup (many) gooks in the tree line”, and that they were starting to move westward out into the open rice paddy area, heading toward An My.

The enemy was starting to cross on the exact same trail they had used on both the 31 January and 10 May encounters with Team 2. Luse quickly radioed a fire mission into the artillery fire direction center (FDC) in Phu Loi, confirming the grid coordinates and direction to the pre-plotted concentration, targeting the point where the target trail met the tree line behind Dog Leg ( a number of pre-plots having been established earlier that day with the Division Artillery FDC as part of the pre-mission planning). . He advised the artillerymen that the target would be “enemy in the open”, and requested “Victor Tango” (variable-time fused, airburst shells).

He also told them to hold their rounds until he called for the firing to commence, as he wanted to get as many of the enemy as possible into the open rice paddies and cut off their line of retreat back into the tree line from which they were now emerging. Now both he and Liesure began softly counting out the VC/NVA group which by now had begun to depart the wood line in force: “10, 20, 30, 40, 50….”, until they had counted over a hundred enemy, with more continuing to come out of the woods into the open paddies. The truck, which could now be seen to be carrying what appeared to be a 12.5mm heavy machine gun in its bed, still remained at the back of the column, just barely into the rice paddy. It was now obvious that the LRRP’s gamble and patience had paid off, and at least a full enemy battalion had chosen this night and place to make its crossing southward around Phu Loi.

With over 200 of the enemy now well into the open rice paddy area and the column emerging from the tree line starting to thin, Luse called for the FDC to give him a spotting round, and he would adjust from there. The first round hit just beyond the juncture of trail and tree line, and Luse immediately called for the next rounds to “Drop 50, and Foxtrot, Foxtrot, Echo (Fire for Effect). The first five rounds burst like a string of giant firecrackers overhead of the tail end of the enemy column, the airbursts exploding downward, showering them with shrapnel. Luse called for “traversing fire”, having the artillery fire continuously along the east-west axis of the trail, savaging the entire column. One artillery tube was now constantly firing illumination rounds over the enemy formation. The enemy troops were now lying in the rice paddies, but without overhead shelter they were defenseless against the deadly shells bursting just over their heads all along their formation. The artillery, now joined by a battery of 4.2 inch heavy mortars, continued to rake the enemy troops (now clearly visible to human eyes under the light of

illumination rounds). The rice paddy quickly became a slaughter ground, as Luse and Liesure alternated adjusting fire onto any groups or individuals trying to flee the impact area. While the NVA force must by now know that they were under “observed”fire, they did not seem to know from where the rounds were being adjusted, as the LRRPs position was just outside of the ring of light being thrown out from the artillery flares.

Meanwhile, the enemy truck somehow managed to turn round and get back into the wood line, heading south back toward Dog Leg. It was still barely visible just inside the wood line, but as it was now so close to the village, no artillery rounds could be directed onto it. Wanting nonetheless to get the truck and the 12.5mm heavy machine gun it was carrying, Luse and Liesure quickly handed control of the artillery off to Elsner and Anderson, grabbed a couple of LAWs (Light Anti-tank Weapon) and attempted to hit the truck as it passed briefly into an open area approximately 300 yards east of the teams position.

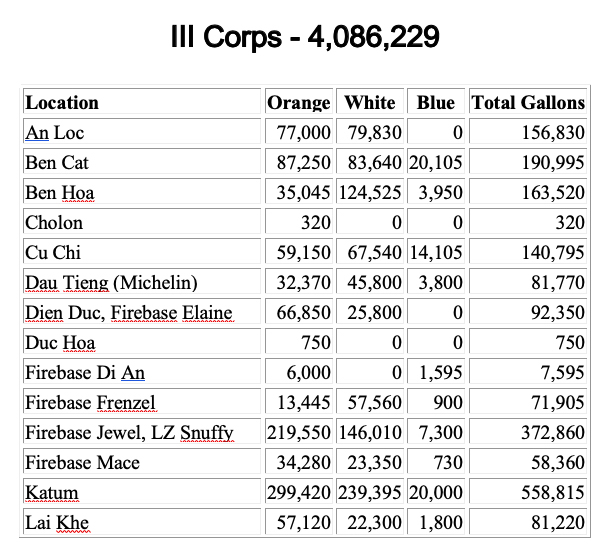

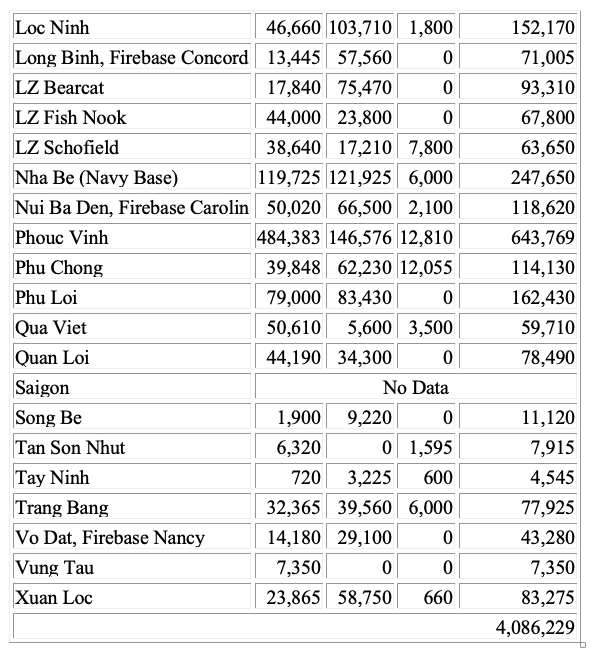

Agent Orange Statisitics

58th Signal Company, 3rd Battalion, 82nd Airborne

605th Transportation Company

610th Maintenance Battalion

612th Transportation Detachment

6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery

74th Reconnaissance Airplane Company

79th Engineer Group, 20th Engineer Brigade, Command

A Troop, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment

Air Cavalry Troop, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment

B Battery, 8th Battalion, 6th Artillery

B Company, 121st Signal Battalion, 1st Infantry Division

B Troop, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division

C Battery, 8th Battalion, 6th Artillery

D Troop, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, 1stT Infantry Division

Dreadnaught Bravo, 2nd Battalion, 34th Armor, 1st Infantry Division

E Company, 701st Maintenance Battalion

E Troop, 3rd Squadron, 17th Cavalry Regiment, Air

Headquarters Battery, 23rd Artillery Group Headquarters

Headquarters Troop, 3rd Squadron, 17th Cavalry Regiment, Air

Revolutionary Development Task Force...

First Liesure, then Luse, tried to align the LAWs alongside the starlight scope and fire at the truck, but both of their rockets missed, the truck escaping into the village. With all of the exploding artillery north of their position, and the VC/NVA troops up there fully occupied trying to escape the artillery impact zone, the LAW firings went apparently undetected, and the LRRPs position uncompromised. But the LRRPs kept at least one starlight scope constantly sweeping the eastern wood line, only 200 meters from their position, for the remainder of the night, as it could provide the enemy with the closest, concealed approach to the LRRP teams’ position.

With no immediate threat to the LRRPs evident, they continued to wreak havoc upon the enemy force in the rice paddies to their north. Disoriented, reeling, and being decimated by the artillery and heavy mortars, the NVA were now faced with yet another hammer blow. Within minutes of the initial artillery barrage, helicopter gun ships of 1st Sqdn/4th Cavalry arrived on the scene and began raking the enemy positions. They were soon joined by a“Firefly” team (a Huey helicopter specially equipped with a powerful Xenon searchlight) and its gunship escorts, who began hitting the enemy troops with rockets, mini-guns and the machine-gun fire of their door-gunners. As they continued to hit the VC/NVA troops, taking sporadic rifle and machine gun return fire, they reported “many bodies” under them, and continued to fire at all enemy troops, moving or not, being unable to tell the living from the dead from the air. After expending all of their ammunition the gun ships withdrew, leaving the field again to the artillery and heavy mortars out of Phu Loi.

The LRRPs continued to keep the enemy force under fire for the next several hours. Team members traded off throughout the night, manning the starlight scopes and calling for additional rounds each time fleeing troops or any movement was spotted, their position in the graveyard apparently still undetected by the VC/NVA. So long as the artillery and mortars continued to hit any troops moving, the NVA unit would be unable to make its exodus from the rice paddies.

At approximately 0400 hours, the LRRPs heard rockets and mortars being fired from behind the eastern wood line, and called a warning into the FDC that the rounds were apparently heading for Phu Loi, also giving an estimated grid coordinate and azimuth to the enemy rocket and mortar firing points. After firing some counter-mortar rounds, the FDC advised the LRRPs that they “were going to ‘check-fire’ to give the artillery and mortar batteries a rest, but would bring in a “time-on-target” (multiple batteries fired in timed sequence so that all of their rounds would arrive at the target at exactly the same time), just before dawn”. The FDC told the LRRPs that they could expect some relief in the form of tanks and ACAVs (tracked armored cavalry vehicles) from 1st Squadron/4th Cavalry, by first light. They further advised that an Air Force FAC (Forward Air Controller “spotter” plane) would come on station for the remainder of the night to cover the ambush site and the area around the teams. Luse and Liesure furiously protested this to the FDC, knowing that without the pressure of the constant and accurate artillery and heavy mortars, the enemy would remove most bodies and weapons from the rice paddies. Given this respite, it was also possible that the VC/NVA might even recover enough to start seeking out the LRRPs, since such accurate and sustained artillery fire certainly had to indicate to the VC/NVA that they were being hit by observed and adjusted artillery. Like it or not, the LRRPs would have to “sit tight” until dawn and the 1st/4th Cavalry unit arrived to reinforce them and sweep the battlefield.

The FAC arrived on station and shortly after first light, reported spotting a large enemy force moving northeast in the tree line on the opposite side of Dog Leg Village from the LRRPs, but too close to the village to bring in either air or artillery. Shortly thereafter the artillery “time-on-target” (TOT) came into the original crossing area, devastating any remaining enemy soldiers—though by that time the LRRPs were sure that most NVA that could move had already vacated the rice paddies during the hiatus in artillery fire.

Following the TOT, Luse and Liesure asked their Phu Loi control if the LRRPs could move out to sweep the battlefield before any more enemy could move into the relative safety of the adjacent tree line. Phu Loi denied them that action, telling them to “sit tight until the Cav arrived”. Finally, about an hour after sunrise, the LRRPs could hear the clanking of tracks and soon the ACAVs and tanks arrived at their position. The LRRPs scrambled from the graveyard and moved out in a line of skirmishers, interspersed between the armored vehicles, and the American force moved north to the crossing point. A few bodies were immediately discovered and some shots rang out from the LRRPs or armor as individual NVA attempted to bring their weapons to bear, thus sealing their fate.

The American force next swept into the eastern wood line, behind Dog Leg, finding a few wounded enemy soldiers and some unwounded ones (or possible villagers, who had unwisely chosen to move out to their rice paddies to begin the day’s work). Hill found one Vietnamese squatted behind a hedgerow and moved him at gunpoint over to a waiting helicopter, which G-2 had dispatched to pick up prisoners for interrogation. Any other Vietnamese found in the area were likewise rounded up and herded over to subsequent helicopters sent in for prisoner pick up. But the lapse in artillery fire had obviously allowed the NVA to move many of their dead, wounded and weapons from the open rice paddies. The LRRPs and their small armored escort would now have to assume the role of sweeping infantry if contact with the badly hurt enemy force was to be regained.

After about a half-hour of this sweeping activity, both Luse and Mills spotted some individuals to the north, one group running southwest toward An My and the others fleeing back in toward Dog Leg. Luse and Liesure quickly decided to split the teams for the pursuit. Luse took most of his team onto the back of a tank and sped after the group fleeing toward An My. (CUT)Elsner advised Luse that he would go with Liesure’s team, to provide additional firepower and security for their smaller team, and quickly moved to catch up to the end of Liesure’s column as they departed to the east with their own armored escort. Luse’s team and their armored contingent continued their chase, however they could not move quickly over the rice paddy berms, for fear of throwing its tracks. The tank commander also refused to fire his main gun at the fleeing Vietnamese, not having clearly identified them as enemy. Frustrated, the LRRPs fired their own weapons at the fleeing Vietnamese, not having any doubts as to the identity of those fleeing. Though the chase continued for a while, the fleeing Vietnamese were able to stay out of small arms range, and with no fire from the tank’s main gun, they finally were able to make it to the village and contact was lost. The Americans thereupon turned back toward Dog Leg—empty-handed.

Meanwhile, back near the village, the lead tank supporting Liesure’s team stopped and reported movement in a small patch of jungle to their front. Leisure and Anderson jumped off of the tank and flanked the area of movement, covered by the armored vehicles. They suddenly spotted four NVA, who, apparently focused on the tanks and tracks, failed to see the approaching Team 1 LRRPs. Liesure and Anderson dropped all four of the enemy, instantly killing two and mortally wounding the other two. Liesure positioned Hartsoe on the south end of the thicket to cover that area, then he, Anderson and Ferris moved up along the east side of the thicket looking for more enemy. Liesure quickly spotted an enemy body about 5 meters into the thicket and he and Anderson went in to investigate, leaving Ferris and Elsner just outside to provide security. Liesure, Anderson and a Cav medic, continued looking for wounded VC, while searching the dead enemy soldier’s equipment looking for information of intelligence value. Elsner was dispatched further up the east side of the thicket to see if any enemy was trying to escape out the “back door”.

Elsner had just started away when he heard Anderson shout: “I’ve found another one”. Elsner again moved back to Liesure and Anderson to provide security while they searched the newly discovered bodies and equipment.

Seeing no more bodies, Elsner advised Liesure that he was returning to his original mission to secure the northeast flank of the thicket. Just as he reached the northeast corner of the thicket, Elsner spotted a small

clearing inside the brush and several dead or wounded enemy in what appeared to be a possible field aid station. He also noted that one of the wounded or dead, who appeared older than the others, had been placed

off to the side from the others—possibly in deference to officer status. Still within earshot of Liesure and Anderson, he yelled out his finding, and Liesure called back for him to “Hold On”, as he and Anderson finished

checking their immediate surroundings.

An armored cavalry track had now also moved into position near Elsner to provide additional security, and the track commander yelled his concern to Elsner that they did not have sufficient security to continue the search in the thicket. Elsner yelled out that he also thought they definitely needed more infantry support in view of the number of bodies they were now finding. Elsner then turned to look back toward the “aid station”, just as three enemy soldiers rose up out of the brush, starting to level their rifles at him. Elsner reacted with his M-60 before the VC could bring their rifles to bear, cutting them down first, while simultaneously yelling out: “I’ve got some more VC!”. At this point, either as a coincidence or due to the shooting taking place at Elsner’s position,

other previously undiscovered enemy soldiers opened up on Liesure and Anderson.

Anderson suddenly heard shots and Liesure was flying back towards him through the air, screaming: “Oh my God Andy”. Anderson quickly tried to release the safety on his M-14, but before he could get a shot off,

found himself spinning like a top, hit in the back and hand. He landed on his right side, and screaming: “Oh my God, I’m dying”, he felt his leg shoot straight up in the air. Realizing that he was still alive, he attempted to grab his rifle, which was laying just to the left of him. However, his right hand had been mangled by the enemy volley, so he quickly grabbed the rifle with his left hand and fired, emptying his magazine into the bush from which his assailant had fired. The enemy soldier, apparently in the process of reloading his weapon, never completed the task, as Anderson’s bullets caught him in the chest. Anderson attempted to load a fresh magazine into his weapon, but found that his spare magazines had been shot up, probably saving his life in the process by blocking the enemy rounds which would otherwise have caused additional hits in his back. Unable to move due to his wounds, Anderson could only stare at the still living apparent NVA officer they had originally gone after. Though the NVA had a pistol, and could have shot Anderson before help arrived, for some reason, he chose not to do so.

Chris Ferris, who had been just outside the thicket behind Anderson, ran in to support Liesure and Anderson. Hartsoe and Elsner also hurried over to provide cover, checking and confirming that Anderson’s return fire had indeed killed the VC who had shot Liesure and Anderson. The Cav medic tried vainly to resuscitate Liesure, but Jack had been hit by the brunt of the enemy fire (the remaining rounds being directed at Anderson) and could not be saved. All of this action, from the LRRP’s initial discovery of the bodies in the thicket, through the subsequent firefight, had taken only minutes. The time between Liesure and Anderson being hit, and the arrival of their teammates only seconds--but to Anderson, in great pain and unable to move, it seemed like an eternity.

After the LRRPs and medic had withdrawn, carrying Liesure and Anderson, the Cav armor fired numerous heavy machine gun numerous rounds into the thicket and torched it with a flame-thrower prior to completing their

sweep.

Luse’s team, not yet back together with Team 1, found out about the loss of Liesure and Anderson via radio. By the time the armor and teams had linked up again, Liesure’s body and the wounded Anderson had already been taken out on a “Dust-off” (medical-evacuation) helicopter. It was a devastating loss to the LRRPs. No amount of “body-count” could atone for the loss of two of their finest. Jack Liesure had been due to depart on 12 May for the LRRP’s base camp, Lai Khe, and begin out-processing for return to the United States—having nearly finished his year-long tour of duty. Anderson was on the “extension” of his tour, having served in an infantry battalion of the Big Red One (1st Bn/26th Inf.) on his first tour. Team Wildcat 1 now had only two surviving members, Charlie Hartsoe and Chris Ferris. Though additional pockets of enemy dead were found in the patches of jungle behind Dog Leg, with an estimated 88 NVA killed in the action, by LRRP standards, the price had been extremely high.

What could have been a clean-sweep for the LRRPs, had been beset by a number of factors largely beyond their control. The early morning cessation of fire by the artillery, allowing the NVA to move most of their dead, wounded and weapons from the artillery ambush site; the lack of regular infantry support, which could have totally sealed off the battle area; even the use of LRRPs to conduct a post-battle sweep operation with a few armored vehicles, despite the knowledge that an approximate enemy battalion had been hit by them on the night and early morning of 11-12 May. The result had been the needless loss of Liesure and Anderson. In the LRRPs’ opinion, it had all added up to a bad trade-off in casualties.

Aftermath

Luse brought Hartsoe and Ferris temporarily under his team and returned to Phu Loi for the debriefing by Division Artillery G-2. The teams then went back to their hootch to grieve, talk about the battle, and plan their

next course of action.

It was quickly agreed with G-2 that the remaining LRRPs would go out again that same night, and see if they could hit the enemy one more time, again in a most unexpected manner. Recruiting a M-60 team from the Phu Loi security force, Luse led his remaining eight LRRPs and the M-60 team out on a final mission back to the same area they had ambushed the previous night. This time, however, the LRRPs would go out to the actual impact area/crossing point of the previous night, and set up their ambush to take any crossing NVA under a direct ambush.

Departing the Phu Loi perimeter after dark, they moved out into the open rice paddies, and set up behind a gravestones actually alongside the expected crossing point trail running between Dog Leg and An My. They felt that they could stop even a sizeable enemy formation, supported by artillery and helicopter gun ships from Phu Loi, if the NVA tried yet another crossing at the same site. Overly aggressive; suicidal? Not in their view, as it was felt that the element of surprise (the LRRPs being once again at a most unexpected site) would certainly favor them, and with two machine guns and massed supporting artillery and air, they were confident they could accomplish the mission without additional casualties. Unquestionably, however, the quest for vengeance also had a bearing on this plan for the night of 12 May. At any rate, it proved to be a fruitless effort, as no contact was made that night, and the LRRPs headed back to Phu Loi before first light.

That the NVA continued with their infiltration through the area northeast of Phu Loi became obvious on the night of 12-13 May. At just after midnight of 13 May, only 10 kilometers to the east of the LRRPs 11-12 May action, the 1st Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR), defending Fire Support Base “CORAL”, were hit with mortars, rockets and ground attacks by the NVA 275th Infiltration Group. Originally headed toward Saigon, this NVA unit, its scouts seeing what appeared to be only a lightly-defended artillery firebase, had decided that CORAL would make a good “target of opportunity” for them. Only after they had commenced their ground attacks did the NVA discover instead that FSPB CORAL was in actuality amply defended by elements of a seasoned and heavily-armed Australian regiment. The NVA ran into a curtain of steel put out by the Aussie infantry, its artillery using “beehive” rounds in direct fire, and air support provided by a “Spooky” DC-3 transport gunship, firing mini-guns round the perimeter. A sweep of the area on the morning of 13 May found 57 NVA dead and numerous individual and crew-served weapons.

Conclusions

Though Teams Wildcat 1 and Wildcat 2 had conducted the artillery ambush throughout the night of 11-12 May, receiving absolutely no infantry support, Division after-action reports did not even connect the LRRPs with the event. Credit for the devastation wreaked upon the NVA that night went to a Division infantry unit which had not been within 10 kilometers of the action. The size of the enemy unit attacked by the LRRPs could not have been in doubt. Even before the sweep of 12 May, the helicopter gunship teams on the night of 11 May had reported spotting “many bodies and wounded” under them in the rice paddies. And the large NVA body count reported by the LRRPs and Cav unit on the morning 12 May lent further proof of just how large an NVA unit had been encountered. Many LRRP operations were “classified” during this period, and that may, in part, account for this historical oversight. However, the irony cut deep. For it was later discovered that several U.S. or allied infantry units were within a half-hour heli-lift from the LRRPs ambush site. While 1st Division infantry battalions were already deployed in response to the continuing “Mini-Tet” Offensive, it would seem that good use could have

been made of at least one of them, with so obviously a large and damaged NVA unit “there for the taking”. Yet, though they were ideally suited for the large-unit “cordon-and-sweep” actions that should have been employed on the morning of 12 May, no infantry was ever brought in to exploit the LRRPs’ artillery ambush. Were the American infantry units all otherwise engaged? That may never be known, but certainly the NVA battalion being destroyed by the LRRPs would have been an ideal target for one of the Division’s heavily-armed infantry battalions, and the odds would have continued to favor the Americans in that case. Ten LRRPs and a half-dozen armored vehicles was not a suitable force for pursuing a badly wounded but still dangerous enemy battalion, but it was the only American force on the scene and, to their credit, neither the LRRPs nor the small cavalry unit failed to “carry on with the mission”.

...